Week 4: Relationship-Building Emails

Once again we’ll start by orienting ourselves to where we are in the journey.

So far we have:

- Established an overall theme that informs and connects the prospects’ experiences with us from initial awareness through conversion (purchase or some equivalent method for idea validation).

- Set the frame that determines what’s possible, meaningful, and perhaps counter-intuitive in the world we’re inviting prospects into.

- Described a compelling, attractive view of our world that leads our ideal audience to want to know even more.

- Required prospects to actively take a step towards us by opting in to continue the conversation by email.

At this point, it’s (very) tempting to ‘strike while the iron is hot’ and go for the sale like a second-hand car salesman. We have their attention (they opted in!) — let’s not waste the opportunity.

Right…?

Not so fast, tiger.

To explain why, a slight detour is required for context and framing.

All of life comes to us in narrative form of a map already drawn, a story already told, a hypothesis, a subjective construction of our own making.

Our “map” represents our biases — of which there are many — beliefs, understanding, and paradigm of our world, all wrapped up in narrative form (the stories we tell ourselves).

The fact that someone we’ve specifically targeted, who has read our ad, clicked, read our landing page, then opted-in for more, now finds themselves in our email world, says a lot.

We can’t emphasize that enough. It gives us some clues, and it presents us with a powerful window of opportunity.

Contrary to how the broad majority of marketers behave, this window of opportunity is not to close a sale as quickly as possible before attention is lost forever.

That scarcity-minded thinking is a red herring the broad majority of marketers fall for. They see the bait, so they take it hook, line, and sinker.

For the one percent (of the .1 percent, perhaps), we see what everyone else doesn’t, the sleight of hand, the illusion.

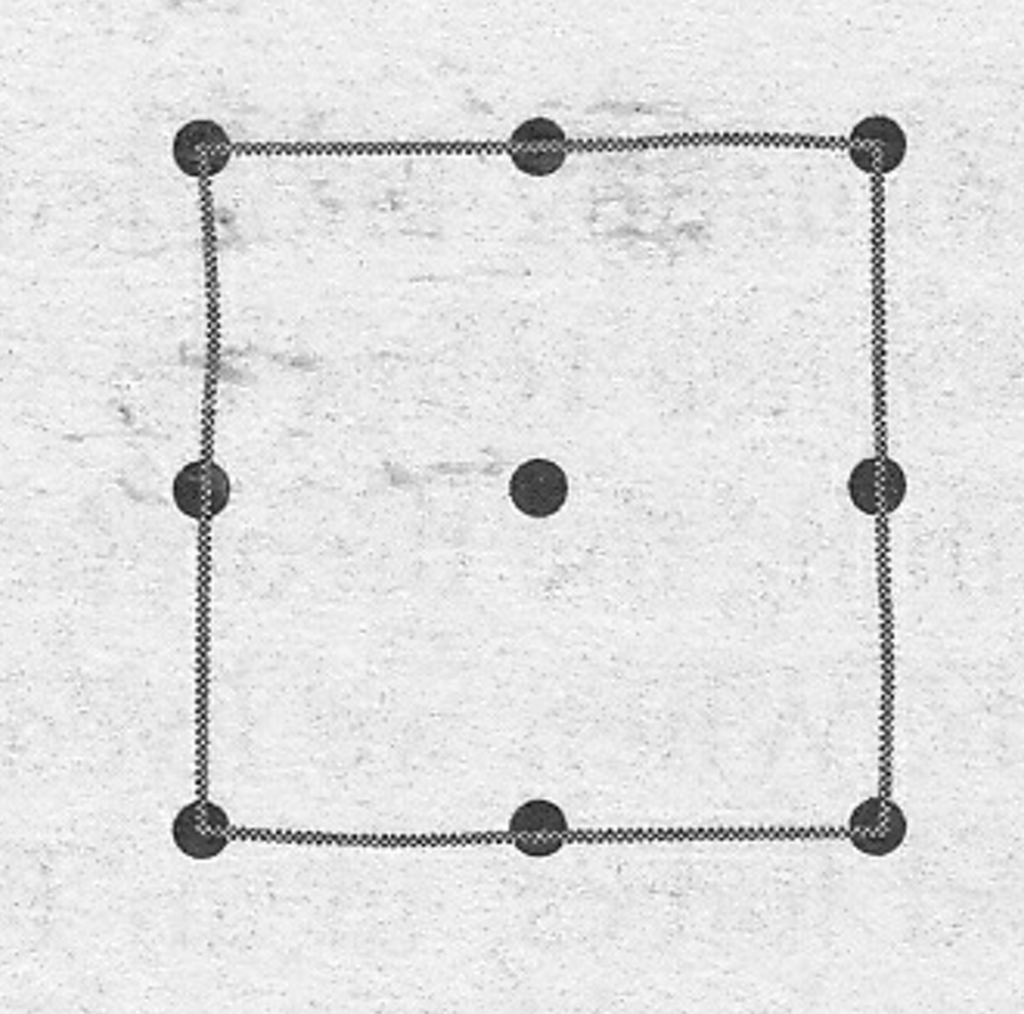

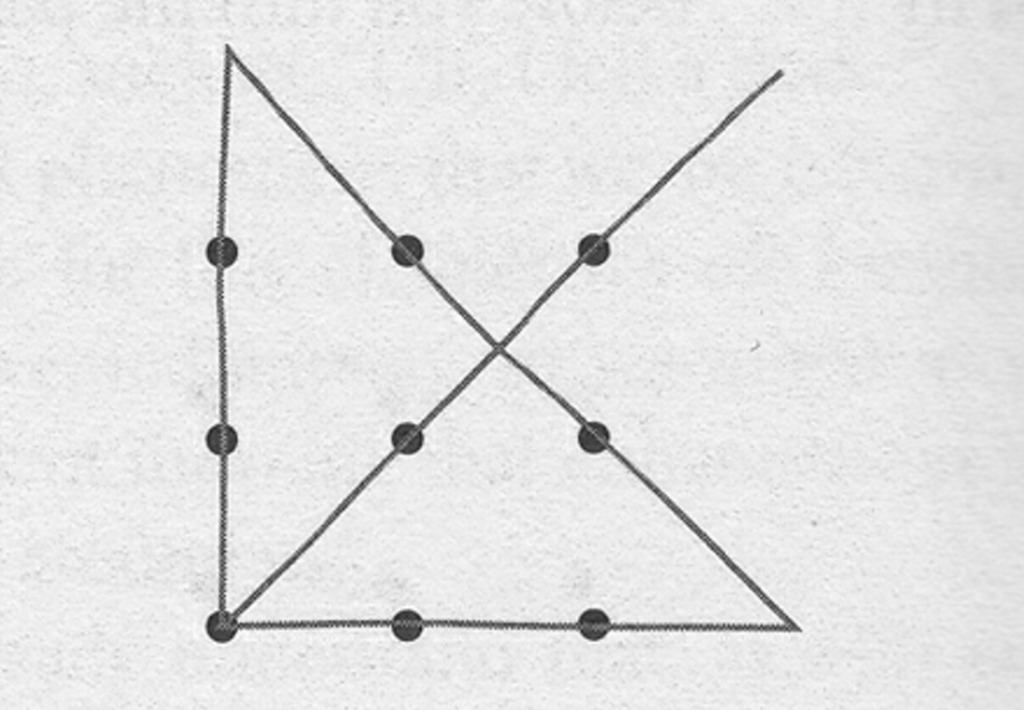

Taken from the book, The Art of Possibility, this simple puzzle reveals how easy it is for us to be “tricked/fooled” when we look for what isn’t there.

OBJECTIVE: Join all nine dots with four straight lines, without taking pen from paper.

If you have never seen and tried this puzzle before, you will most likely find yourself struggling to solve the puzzle inside the space of the dots, as though the outer dots have constituted the outer limit of the puzzle.

The puzzle illustrates a universal phenomenon of the human mind, the necessity to sort data into categories in order to perceive it.

Your brain instantly classifies the nine dots as a two-dimensional square. And there they rest, like nails in the coffin of any further possibility, establishing a box with a dot in each of the four corners, even though no box in fact exists on the page.

Nearly everybody adds that context to the instructions, nearly everybody hears: “Connect the dots with four straight lines without taking pen from paper, within the square formed by the outer dots.” And within that framework, there is no solution.

If, however, we were to amend the original set of instructions by adding the phase, “Feel free to use the whole sheet of paper,” it is likely that a new possibility would suddenly appear to you. The frames our minds create define — and confine — what we perceive to be possible.

The same is true when new people enter our world (or our email list in this case). As we inferred earlier, each person comes with a map already drawn of their current reality.

The illusion of the opportunity is to sell them as quickly as possible before leaving and never returning.

But, as with the nine-dot puzzle, the solution lies outside of our default direct response marketers mindset or frame.

The real window of opportunity is to form a bond, an authentic relationship, to build rapport, and establish credibility and authority — first.

We want our audience to know, like, respect, and trust us within the context of the journey we’re on together.

When we accept this, embrace it as a core principle, everything changes downstream. Everything we do will be easier and demonstrably better.

This is why we want to build relationships with prospects before we allow our audience to buy something (anything!).

For the purposes of this workshop, we’ll do that over three emails, in narrative form — one per day over three days.

This is an important nuance — we’re not just “telling our story” — we’re telling our story as it relates to the reasons why they might be interested.

For example, if you’re a digital marketing service provider, you want your audience to know, like, respect, and trust your guidance primarily as it relates to digital marketing.

It’s not as much about that trip you took with your fishing buddies or the funny thing your daughter did at breakfast last week.

We certainly can include some of the lighter fare, as long as it doesn’t distract from the central theme and purpose.

Stories can be a great lead-in if they can be tied into our marketing message to help demonstrate a lesson or visualize an idea in a meaningful way like metaphors do.

(Pro tip: the P.S. section is an excellent place for the more personal revelations. Just remember that everything you write is in service to the entire journey from the prospects’ perspective, so choose wisely, and respect their attention.)

Second, we are continuing to create and resolve tensions that pull our prospects forward. This becomes more powerful because our canvas is larger.

Instead of a single piece of writing (an ad or a landing page), we have three opportunities to interact (and a 24-hour gap between them, which can amplify the tension we’re engineering).

Two types of tension-creating devices that are easily accessible are the “open loop” and “cliffhanger.” They evoke similar emotional responses in the reader, but they’re subtly different in their application and timing.

A study by George Loewenstein of Carnegie-Mellon found that we get significant feelings of anxiety when there’s a gap between what we know and what we want to know.

The simplest expression of an open loop is “more about that later,” paired with an incomplete thought that’s then “closed” later in the email (most commonly), or in some cases, in a subsequent email.

A cliffhanger is subtly different.

It’s most commonly used when the end of a scene or episode (or email), just before the climax of an email sequence, is curiously abrupt, usually in a suspenseful or shocking way, in order to compel a reader to turn the page or return to the story in the next installment (next email for us).

For this reason, the best place to use a cliffhanger (only if it makes sense) is just before the central climax of an email sequence. In a seven email series, that would likely be email five or six.

Here’s a simple example of an open loop:

“In our experience as writers, there are three things that differentiate good writing from bad writing. We’ve learned these lessons the hard way, over decades of writing, making more than our fair share of mistakes along the way.

We’ll share those three things later because they won’t make sense if you don’t understand the context.”

(Bold is only to highlight the open loop device, we don’t recommend that you actually bold your open loops.)

That’s a (very basic) open loop.

There’s a promise of something interesting, a little dash of credibility, and a tablespoon of humility — all of which create a little tension. Then there’s the explicit mention that the tension will be resolved…later.

Keep in mind that there are infinite ways to create open loops — many of which are obvious (and relatively easy), and others that are much more subtle (which can be far more potent in how a reader is affected).

However, take our advice and lean towards the obvious for now.

Don’t let wordsmithing and overthinking the many nuances of writing well get in your way of creating something of value for you and your audience.

As your writing skills evolve and you stay focused on the thematic arcs guiding your work, you’ll naturally develop your own toolkit for opening and closing loops.

Third, our relationship-building emails are in service to the eventual sale.

We can hear your collective gasp — WHAT?

We’re deceiving our audience?

Tricking them into thinking we’re decent people only to make a buck?

No, that’s not (at all) what we mean.

What we’re saying is that we ultimately want the right prospects to know, like, respect, and trust us so that we are best positioned to create a meaningful exchange of value after we’ve developed the relationship.

We also want to be so clear about who we are, what we believe, and who we help that anyone who is not an ideal prospect will self-select out of our world along the way.

This brings us to two critical insights that we believe will help you understand your marketing (and your writing) from a much more powerful perspective.

Insight #1 — knowing, liking, respecting, and trusting another person enough to make a purchase are emergent properties of your entire marketing system. They’re not things we do, boxes to check (and in this week’s lesson, solely emails to write).

The way you’ve written your Facebook ad and landing page has set the stage for the relationship. You’ve shown your ideal audience a different way to see an issue they’re struggling with — that could be a discomfort in their life they want to eliminate or diminish or a desire they want to move toward or fulfill.

Let’s be clear — the way you’ve approached your writing has been an act of service and value, not persuasion (or coercion).

Goodwill emerges from those efforts (for the right people at the right time) because of that approach.

After someone has taken a step towards us by opting in to receive our emails, we’re continuing the journey they’ve been on in a way that’s congruent and comforting (being pulled forward with tension, as if they are tied to an invisible elastic band).

There’s no immediate hard sell. Instead, the tone, pace, and respect for the reader remains (forever).

We provide more context about our background, how we learned what we’re sharing, and what we’ve discovered along the way. And we may share some of our missteps, where we went wrong, and how we fell down (which demonstrates empathy; I see you, I hear you).

The entire time we’re building toward something of value for THEM — creating and resolving tension building toward something that they want (but has not yet been revealed).

You can choose to do that like the proverbial ‘sage on the stage’ or the ‘guide on the side.’

The sage positions herself as the expert to be followed because she has done the work to know what works and what doesn’t.

Guides take their audiences along journeys they’ve been on to share what they found along the way.

Sage or guide?

There’s no right answer — there’s the right answer for you based on your individual experience, strengths, and communication preferences.

Insight #2 — the most important loops you open during the prospects’ journey should only be closed by the purchase of your offer (these loops are almost always implied within the subtext of your email series).

This is critically important and difficult to understand.

The creating and resolving of tension is a rising and falling in service to a goal that you know about in advance, and your prospect does not. S/he is feeling a magnetic pull towards something unseen (your offer).

The best way to understand what this feels like is to listen to Ben Zander explain a Chopin prelude in The transformative power of classical music.

(Trust us — don’t skip the video. Soak it in.)

In practice, we’re continuing to direct the reader toward the value we’re able to create — for them — by implicitly and explicitly directing their attention to the reveal of an offer that happens LATER (first on day #4, or whenever you reveal your offer in your specific campaign).

When we finally reveal the offer, the prospect should feel the same way that Zander’s audience felt when he played the final note in the Chopin prelude … ah, I’m home…

How do you do it?

Here’s your homework.

You’re going to write three separate emails that are approximately 600-1,000 words each.

(Every market, audience, pocket of people — and how you’ve brought them into your world with your framing and context — will have a different level of attention and interest, hence the 600-1,000 range. This is not a rule, just a ballpark number to aim for.)

To do that, you’ll need lots of ingredients in the form of ‘beats’ (which we described in detail here).

Beats should be brief — they’re short sketches of an idea (often expressed as single sentences that make sense to you but not necessarily the reader).

For example:

“Story about Top One big idea award” makes no sense to the reader, but that’s a beat Shawn included in his original description of the backstory of The Traffic Engine.

That beat pointed the way, and the writing (that made sense to the audience) followed.

Your beats should include elements of your journey — successes, missteps, revelations, and the occasional tangent.

How did you learn about what you’re sharing with your audience?

What was meaningful to you?

What did you believe at the beginning of your journey that you no longer believe?

How has your life changed because of what you’ve discovered?

Don’t edit — just get your beats out of your head and onto the page (or the screen).

You will want to digitize these beats so you can move them around easily. They’ll become the signposts for what you’ll write in the three relationship-building emails.

Arrange the beats as well as you can in advance, and then write and notice where your outline may be off (and adjust as necessary). Beats point the way, but they’re not handcuffs.

Often a structure looks right in outline form, but the writing doesn’t flow as well. Make the necessary adjustments on the fly.

By the end of three emails — and approximately 2,000 — 3,000 words — your personality, glimpses of your history as it relates to the context of your offer, and the quirks that make you human should be visible.

This is hard work, and yes, it’s scary.

But it’s also meaningful and a critical step in bringing your value into the world for the people who need it most.

If it’s helpful, use this popular storyboarding technique from ARM. Open up four text windows across your screen like this (TextEdit for Mac and Notepad for Windows are two free option available to everyone):

Add your beats, any ideas you have outside of your beat structure, and any insights that emerge as you write to the first text document.

If you are anything like us, who “think on the page,” all sorts of ideas and insights will bubble up when you start to write. Don’t let these distract you; jot down the idea in the left-hand document, then continue to write without editing until you’re done.

(Pro tip: Turn ‘Check Spelling While Typing’ off. Only turn on auto spelling and grammar after you’ve birthed your shitty first draft.)

So get to work.

If you’d like us to consider your emails for review / critique, please submit those (by email) before midnight, PST on Sunday, April 11.

Note about homework: Please use something like Google Docs or Notion for your email sequence, then paste the link to it in the comments below.

Feel free to post questions in the comments below.

Finally, listen to the audio we recorded specifically for this week as well before you write.

Unscripted Audio Narration

Our audio conversation will only be useful after you’ve read this lesson, so read the lesson first.

Week 4 Feedback (April 14, 2021)

This week we reviewed the relationship-building email sequence from Coen van Broekhoven (Google Doc).

It’s a wide-ranging discussion we feel will be broadly useful to everyone.

Links to different types of nonfiction writing from our discussion:

- Russia Beat the World to a Vaccine, so Why Is It Falling Behind on Vaccinations? | The New Yorker (journalistic piece)

- George Saunders: what writers really do when they write | The Guardian (how-to piece from an award-winning author and professor of writing at Syracuse University)

- Donald Trump and the Rules of the New American Board Game | Vanity Fair (a piece by Michael Lewis)

- The Ketchup Conundrum | The New Yorker (piece my Malcolm Gladwell)

- (An archived version.)

.— André & Shawn